Various pricing approaches and strategies are available to the marketer. How do you find the right pricing strategy for your products? At first, it is essential to get an overview of pricing strategies. In the following, we will investigate the most common pricing strategies in detail and provide an overview of pricing strategies.

Overview of Pricing Strategies

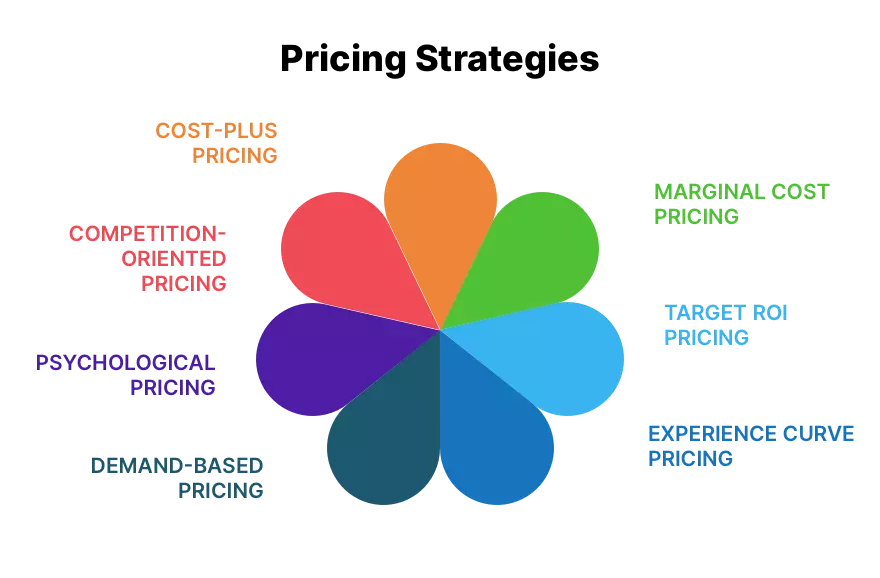

There are seven pricing strategies that we will explain in more detail in the following.

The diagram below gives an overview of pricing strategies.

Cost-based pricing

In setting a price, it is (in normal cases) advisable to cover all relevant costs. Costs for this purpose may be divided into two categories, fixed and variable costs. Taken together with price, these costs can be used to calculate the break-even quantity: fixed costs divided by the contribution margin (price less variable cost per unit).

The four most important cost concepts are fixed costs, variable costs, marginal cost and total cost. These types of costs are explained in the following:

- Fixed costs are those costs that do not vary with output (at least in the short term). This category includes for instance salaries, insurance, rent, buildings and planned machine maintenance costs. Once output passes a certain threshold, however, extra production facilities might have to be brought on stream and so fixed costs will show a step-like increase.

- Variable costs are those costs that vary with the quantity produced. These costs are incurred through raw materials, components and direct labor used for assembly or manufacture. Variable costs can be expressed as a total or on a per-unit basis.

- Marginal costs involve the change that occurs to total cost if one more unit is added to the production total.

- Total cost refers to all the cost incurred by an organization in manufacturing, marketing, administering and delivering the product to the customer. Total costs are the sum of fixed costs and variable costs.

Cost-oriented pricing is the most elementary pricing method. It involves the calculation of all the costs that can be attributed to a product, whether variable or fixed, and then adding to this figure a desirable mark-up, as determined by management.

The simplicity of this method is that it requires no other effort beyond consulting the accounting or financial records of the firm. There is no necessity to study market demand, consider competition, or look in to other factors that may have a bearing on price. Cost is considered the most important determinant in the firm’s pricing effort, which is then directed towards covering these costs and realizing the desired profitability.

Cost-plus pricing is popular among many retailers and wholesalers. For example, in the case of retailers, the purchase price of the product is added to the product’s share of the operating expenses and a desirable margin, determined by the type of product under consideration, is then added to determine the selling price.

Marginal cost pricing

Marginal cost pricing is a rather close approach to cost-plus pricing in the overview of pricing strategies. In cost-plus pricing, the margin set reflects all the costs and overheads attributed to a particular product or service. In marginal cost pricing (often called marginal pricing) only a proportion of the costs (those directly attributable to the production of the item under consideration) is included in the price. The fixed costs of production, e.g. the rent of the building, are discounted and only the variable costs, e.g. direct materials, direct labor, etc., are included. This means that the cost is less than might otherwise be expected and a more competitive price can be charged.

Marginal pricing is useful when a company has short-term excess capacity. In the long term it is inappropriate because all costs must be covered – otherwise the company will go out of business. Another disadvantage of marginal pricing is that existing customers may be irritated to learn that a competitor, or another group of customers, has been offered a reduced price.

Despite its simplicity, there are a number of weaknesses in the cost-plus pricing and marginal cost pricing approaches that limit their practicality. The price an individual is willing to pay for a product may bear little relation to the cost of its manufacture. Studies of consumer behavior have produced considerable evidence that contradicts the assumptions of classical economists, in that the consumer as a wholly rational buyer may knowingly select a product or service at a higher price, even though substitutes may be available. This is particularly true with status items such as designer clothes, sports cars and first-class travel. An investor in diamonds, art or stamps does not value the object in question in terms of its costs of production or extraction, but rather in terms of its value to him/her.

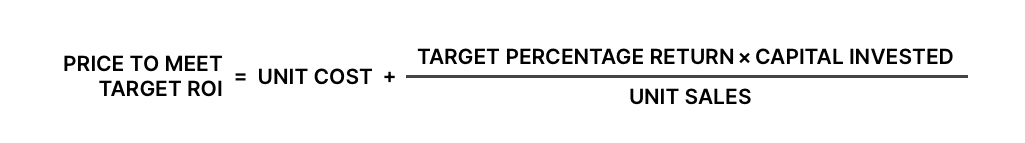

Target return on investment pricing

We continue our overview of pricing strategies with target ROI pricing. This is similar to cost-plus pricing as it assumes that costs can be known or estimated with enough accuracy to feature in the calculation of price. Target pricing, which looks for long-run average rates of return, is one method of cost pricing, used especially when fixed costs at launch are high. Among those who have used this in the past have been the privatized utilities and, in the US, General Electric and General Motors. The calculation is straightforward:

This approach to pricing is prone to the same difficulties as any cost-based approach, but it has the advantage of forcing consideration of whether a proposed price is feasible from a purely commercial point of view.

Experience curve pricing

As organizations produce more units, experience and learning lead to greater efficiency. The sources of the experience effect are varied and include such factors as labor efficiency, as the assigned tasks are repeated over and over again, and work specialization, as the worker becomes more proficient in performing a single-facet operation as opposed to a multi-faceted one. Unlike cost reductions from capacity utilization, cost reductions resulting from experience are a result of concerted effort by management. For example, the relative prices of fax machines and mobile phones are falling, partly because of the experience curve effect.

Demand-based pricing

Demand-based pricing may be the most important pricing approach in our overview of pricing strategies nowadays. Demand-based pricing looks outwards from the production line and focuses on customers and their responsiveness to different price levels. Even this approach may be insufficient on its own, but when it is linked with competition-based pricing, it provides a powerful market-oriented perspective that cost-based methods ignore.

Demand-based pricing allows the price to go up when demand is strong and, vice versa, for the price to go down when demand is weak. Examples of demand-based pricing can be found within the package holiday industry where prices are highest during the school summer holidays and in the travel industry where prices vary according to the level of demand, e.g. highest during the morning rush hour and cheapest during off-peak times.

This method requires decision makers to make volume forecasts for different price levels and calculations of production and marketing costs at different levels to cover overheads. In setting a price information has to be obtained about demand factors, e.g. the price elasticity of demand. This is calculated by estimating the percentage change in quantity demanded over the percentage change in price. By gaining knowledge of demand factors the marketer helps avoid the potentially disastrous mistake of focusing too much on costs. Typically, this involves estimating likely demand at different prices; estimating what happens to cost as demand rises; estimating the likely effects of raising or lowering price.

Psychological pricing

In using psychological pricing, sellers consider the psychology of prices as well as the economics. When consumers can judge the quality of a product by examining it, or by calling on past experience, they use price less to judge quality. When consumers cannot judge quality because they lack the information or skill, price becomes an important quality signal, as the following case study illustrates.

The following are examples of psychological pricing:

- High-level pricing, usually maintained throughout the entire PLC: prestige items such as fine jewelry and designer clothing use high pricing together with associated advertising that lends an aura of prestige and quality to the item.

- Odd–even pricing, i.e. the practice of ending a price with certain numbers. Odd number price endings like $999.99 for a computer system are seen by customers as a price in the under $1,000 range rather than in the next higher category. If a company wants a high-price image rather than a low-price one, then it should avoid the odd-ending tactic.

- Bundle-pricing, where two or more products or services are offered at a particular price, usually gives a lower price than the total price of all the items sold separately. For example, a fly-drive arrangement for one price, a hotel arrangement including sightseeing tours at a special price or a book of theatre tickets for the season at a cheaper price than if they had been bought singly. The opposite process of unbundling involves breaking up the bundle when conditions indicate it is no longer useful.

Competition-oriented pricing

We conclude our overview of pricing strategies with competition-oriented pricing. Competition-oriented pricing involves setting prices on the basis of what competitors are charging. Once the firm identifies its competitors, it conducts a competitive evaluation of its product. Competitive factors that must be considered include:

- The ‘market price’ charged by the market leader.

- Price sensitivity.

- Market position.

- Product differentiation.

- The type of competition, i.e. whether this is monopoly or oligopoly.

In assuming how a competitor might react to a price move, several factors need to be considered. These include:

- The competitor’s cost structure.

- Past price behavior.

- Market demand.

- The relationship of the product to others in the competitor’s line.

- Plant utilization.

If the cost-oriented approach to pricing is considered to be forward in nature, the competition-oriented method can be thought to be a backward exercise in pricing. Under the cost-oriented approach, prices are determined on the basis of total cost calculation to which a reasonable profit margin is added. In other words, the pricing process proceeds forward with the calculations of variable and fixed costs, to which a desirable return is added to reach a price. Under the competition-oriented approach, price is the starting point in the calculation process. Obviously, this price is only an indication of the appropriate price to charge in view of the competition in the market place, but it has no necessary relation to cost. In this way, the manager works ‘backwards’ from this given price to see if the designated price is sufficient to cover costs and desired profitability.

This overview of pricing strategies should give you a clear idea of the right approach for your firm. As you may recognize, many firms today rely on cost-plus pricing. However, there is a clear tendency towards demand-based pricing. When deciding on a pricing approach, all potential strategies in the overview of pricing strategies should be considered.